According to Galileo, Newton, and Einstein, the classical principle of relativity states that no mechanical experiment can be done to detect absolute motion, or motion of a material object relative to an everywhere stationary medium (similar to Michelson-Morley). A common reformulation of this principle states that:

♦The velocity of any motion has different values for two observers moving relative to each other.

The following thought experiment proposes to investigate this principle, that is, to find if these two values are measurably different, or measurably the same. It seeks to find the particular values of the motion of material object as seen by two observers in separate references frames, one moving and the other at rest, relative to one another. It will measure the time interval between two mechanical events occurring in the moving reference frame. This time interval is measured by two observers each possessing one of two distantly separated clocks. This thought experiment will use sound waves to determine a closely approximate measurement for the time interval between these two mechanical events.

On a windless night (air molecules at rest relative to the earth), a train of length L is traveling at the constant velocity v along a flat, straight section of train track. There is an observer in the caboose (train reference frame) as well as another observer on the station platform near the track (earth reference frame). They each have identical clocks with which to conduct the following thought experiment: they will attempt to detect absolute motion, or at least test the mentioned common reformulation of the classical principle of relativity. That is, to show that two observers can measure the same value for the velocity v of the train using the same formula, without a Galilean transformation, although these two references frames are moving relative to one another.

Placing each observer in separate reference frames which are moving relative to one another then by the Galilean transformation (addition of velocities) a material object will manifest as its velocity:

♦ u` = u – v

where u` is the velocity of the train in the reference fame attached to the train (this is usually zero); u is the velocity of the train in the reference frame attached to the platform; and v is the velocity of the train reference frame. In the reference frame attached to the train, the train itself has a velocity of zero; and in the reference attached to the platform, it will simply have the velocity of the reference frame attached to the train. The velocity of the train is represented by this formula, as well as the velocity of any material object moving within that train; each velocity is seen by the observer sharing the motion of the train, and the observer at rest on the nearby earthbound platform.

The usual method from classical physics for finding the train’s constant velocity v is to measure the time interval that it takes for it to travel between two stationary landmarks a known distance apart (velocity = distance/time). But this method would not work in the darkness of night. If an observer on the train has no access to external landmarks then that observer would have no clues to indicate that the train is in motion. For, any mechanical experiment done when traveling at a constant velocity, such as dropping a ball to the floor, or tossing a ball to a friend in another seat, would proceed as if the train were at rest. That is, these material objects would follow a trajectory through space that does not hint at the train’s motion. The following thought experiment could find the velocity of the train, even at night, without any visible external landmarks on the stationary earth as seen through a window.

If the experiment is conducted in the moving reference frame of the train, then the arm of the human ball thrower transfers a certain amount of momentum onto the ball from the train, thus increasing or decreasing the velocity of the ball. The observer sharing the motion of the reference frame attached to the train would not and cannot measure this momentum exchange, but the observer on the platform will notice this change of the velocity and trajectory of the ball.

However, a sound wave does not mechanically behave in this manner. The mechanical event of a sound wave emission at some point in space, and then the receipt of that wave at some other point in space, will progress in one of two ways. If the experiment were conducted in a closed compartment then the air molecules/medium would have the velocity of the compartment and the moving air will act to increase or decrease the velocity of the emitted wave. This increase or decrease will depend on the direction of the sound wave relative to the compartment, and the emitter’s state of motion or rest within the compartment. But if the experiment were carried out in the open still air then the air molecules will have a velocity of zero which will allow them to pass freely through the “conceptual walls” of the reference frames. Thus, the air will have no effect on the velocity of the emitted sound wave no matter if the emitter is in motion or at rest.

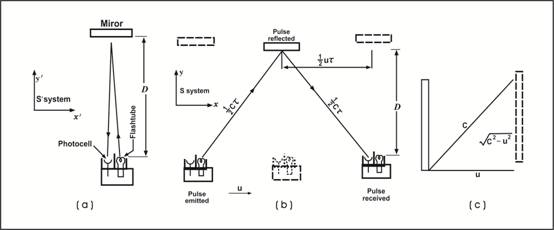

The new method presented by this thought experiment for finding the velocity of the train (material object) relative to the still air (medium at rest – Michelson-Morley), the observer in the caboose has a light source with which she will send a signal to the engineer at the front of the train. He will then blow the whistle, sending out sound waves which the caboose observer will be able to hear. At the moment she sends the light signal from the open caboose window, she starts the single clock that she has. The platform observer will also see this nearly instantaneous signal (the velocity of light is too fast to be measured by a normal clock) and he will start his single clock at the same moment. Thus, their mechanically identical clocks will essentially be synchronized.

Over this short distance, the light signal that the engineer and the platform observer see is approximately instantaneous so that the time t she measures is essentially the time for the sound wave to travel the length L to reach her ear. When she hears the whistle sound she stops her clock and immediately once again flashes her light. The platform observer also stops his clock upon seeing this second flash. Disregarding reaction times, both observers should measure the same interval of time t. Since the speed of the sound wave and the speed of the train are so much slower than the speed of light, the Special Relativistic (STR) effects of time dilation and length contraction are negligible, and will thus have little to no impact on the time interval measurement. The gamma factor cannot dilate the time interval enough or contract the length enough to create the illusion of a resting reference frame in the presence of a sound wave event.

The caboose moves forward to meet the rearward travelling sound wave, so the sound wave will travel a distance that is less than L, the length of the train at rest. The speed of the sound wave does not change, but the motion of the material object (train) is disengaged from the medium (still air). This should lead to, approximately, identical time interval measurements by the observers in each reference frame. This disengagement mechanically permits the air molecules to freely flow between the reference frames which are moving relative to one another. These air molecules easily pass through the “conceptual walls“ of the reference frames, like the ghostly spirits in a haunted house.

The sound wave and the caboose begin their journeys at the endpoints of L. The caboose has the constant velocity v, and the sound wave has the constant velocity c. As the train engine and the caboose move through space they form a tandem, with each car remaining at a fixed distance apart no matter whether the train is in motion, or at rest. An important premise of this experiment is that the sound wave travels between these two endpoints of the train, or alternatively, along the length L. Each observer takes the length L from the train specifications, it is measured when the train is at rest by the traditional units of measurement. Additionally, each observer knows the accepted speed of sound in still air. So, all the variable values are available to the observer within each reference frame. To reflect the conditions under which the caboose and sound wave will meet somewhere between the endpoints of L then the following equation can be set up:

♦The velocity of any motion has different values for two observers moving relative to each other.

The following thought experiment proposes to investigate this principle, that is, to find if these two values are measurably different, or measurably the same. It seeks to find the particular values of the motion of material object as seen by two observers in separate references frames, one moving and the other at rest, relative to one another. It will measure the time interval between two mechanical events occurring in the moving reference frame. This time interval is measured by two observers each possessing one of two distantly separated clocks. This thought experiment will use sound waves to determine a closely approximate measurement for the time interval between these two mechanical events.

On a windless night (air molecules at rest relative to the earth), a train of length L is traveling at the constant velocity v along a flat, straight section of train track. There is an observer in the caboose (train reference frame) as well as another observer on the station platform near the track (earth reference frame). They each have identical clocks with which to conduct the following thought experiment: they will attempt to detect absolute motion, or at least test the mentioned common reformulation of the classical principle of relativity. That is, to show that two observers can measure the same value for the velocity v of the train using the same formula, without a Galilean transformation, although these two references frames are moving relative to one another.

Placing each observer in separate reference frames which are moving relative to one another then by the Galilean transformation (addition of velocities) a material object will manifest as its velocity:

♦ u` = u – v

where u` is the velocity of the train in the reference fame attached to the train (this is usually zero); u is the velocity of the train in the reference frame attached to the platform; and v is the velocity of the train reference frame. In the reference frame attached to the train, the train itself has a velocity of zero; and in the reference attached to the platform, it will simply have the velocity of the reference frame attached to the train. The velocity of the train is represented by this formula, as well as the velocity of any material object moving within that train; each velocity is seen by the observer sharing the motion of the train, and the observer at rest on the nearby earthbound platform.

The usual method from classical physics for finding the train’s constant velocity v is to measure the time interval that it takes for it to travel between two stationary landmarks a known distance apart (velocity = distance/time). But this method would not work in the darkness of night. If an observer on the train has no access to external landmarks then that observer would have no clues to indicate that the train is in motion. For, any mechanical experiment done when traveling at a constant velocity, such as dropping a ball to the floor, or tossing a ball to a friend in another seat, would proceed as if the train were at rest. That is, these material objects would follow a trajectory through space that does not hint at the train’s motion. The following thought experiment could find the velocity of the train, even at night, without any visible external landmarks on the stationary earth as seen through a window.

If the experiment is conducted in the moving reference frame of the train, then the arm of the human ball thrower transfers a certain amount of momentum onto the ball from the train, thus increasing or decreasing the velocity of the ball. The observer sharing the motion of the reference frame attached to the train would not and cannot measure this momentum exchange, but the observer on the platform will notice this change of the velocity and trajectory of the ball.

However, a sound wave does not mechanically behave in this manner. The mechanical event of a sound wave emission at some point in space, and then the receipt of that wave at some other point in space, will progress in one of two ways. If the experiment were conducted in a closed compartment then the air molecules/medium would have the velocity of the compartment and the moving air will act to increase or decrease the velocity of the emitted wave. This increase or decrease will depend on the direction of the sound wave relative to the compartment, and the emitter’s state of motion or rest within the compartment. But if the experiment were carried out in the open still air then the air molecules will have a velocity of zero which will allow them to pass freely through the “conceptual walls” of the reference frames. Thus, the air will have no effect on the velocity of the emitted sound wave no matter if the emitter is in motion or at rest.

The new method presented by this thought experiment for finding the velocity of the train (material object) relative to the still air (medium at rest – Michelson-Morley), the observer in the caboose has a light source with which she will send a signal to the engineer at the front of the train. He will then blow the whistle, sending out sound waves which the caboose observer will be able to hear. At the moment she sends the light signal from the open caboose window, she starts the single clock that she has. The platform observer will also see this nearly instantaneous signal (the velocity of light is too fast to be measured by a normal clock) and he will start his single clock at the same moment. Thus, their mechanically identical clocks will essentially be synchronized.

Over this short distance, the light signal that the engineer and the platform observer see is approximately instantaneous so that the time t she measures is essentially the time for the sound wave to travel the length L to reach her ear. When she hears the whistle sound she stops her clock and immediately once again flashes her light. The platform observer also stops his clock upon seeing this second flash. Disregarding reaction times, both observers should measure the same interval of time t. Since the speed of the sound wave and the speed of the train are so much slower than the speed of light, the Special Relativistic (STR) effects of time dilation and length contraction are negligible, and will thus have little to no impact on the time interval measurement. The gamma factor cannot dilate the time interval enough or contract the length enough to create the illusion of a resting reference frame in the presence of a sound wave event.

The caboose moves forward to meet the rearward travelling sound wave, so the sound wave will travel a distance that is less than L, the length of the train at rest. The speed of the sound wave does not change, but the motion of the material object (train) is disengaged from the medium (still air). This should lead to, approximately, identical time interval measurements by the observers in each reference frame. This disengagement mechanically permits the air molecules to freely flow between the reference frames which are moving relative to one another. These air molecules easily pass through the “conceptual walls“ of the reference frames, like the ghostly spirits in a haunted house.

The sound wave and the caboose begin their journeys at the endpoints of L. The caboose has the constant velocity v, and the sound wave has the constant velocity c. As the train engine and the caboose move through space they form a tandem, with each car remaining at a fixed distance apart no matter whether the train is in motion, or at rest. An important premise of this experiment is that the sound wave travels between these two endpoints of the train, or alternatively, along the length L. Each observer takes the length L from the train specifications, it is measured when the train is at rest by the traditional units of measurement. Additionally, each observer knows the accepted speed of sound in still air. So, all the variable values are available to the observer within each reference frame. To reflect the conditions under which the caboose and sound wave will meet somewhere between the endpoints of L then the following equation can be set up:

♦ L = ct + vt

Certainly, they have measured the same interval of time t in both reference frames. The STR does not account for any time dilation or length contraction at the slow speeds involved here. The observer in each reference frame retrieves the length L from the train specifications. The speed of sound c is assumed to be constant or the same for both observers. Thusly, the formula can be solved for v the velocity of the train as seen from either reference frame:

♦ L = t(c + v)

♦ v = [L / t] – c

A similar argument can be made for the case when the train is moving in the reverse direction, the sound wave is then overtaking the caboose, that is, the sound wave will catch up to the caboose somewhere beyond the caboose’s initial position:

♦ L + vt = ct

♦ L = ct – vt

♦ v = c – [L / t]

The departure and arrival events of the sound wave occur at the same places and at the same times (invariance of coincidence) in space, and is mathematically observable in each reference frame. The above expression contradicts the Newtonian and Einsteinian principle of relativity in that although the two reference frames are moving relative to each other, this experiment allows each observer to use one and the same formula to find the velocity of the train as seen from either reference frame. This results in not needing the addition of velocities from the Galilean transformation between references frames when sound waves are used to investigate the motion of material objects. So, I hypothesize that a new form of motion unveils its mysteries, it is neither absolute motion, nor absolute rest. An intermediary motion of material objects can now be defined, as they travel through the space of our everyday realities.